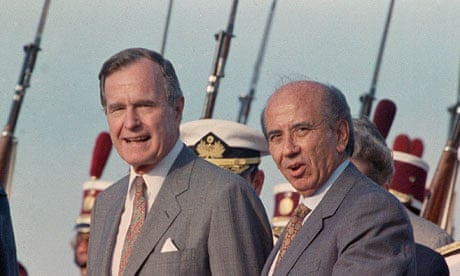

The former Venezuelan president Carlos Andrés Pérez, known to Venezuelans as "CAP", who has died aged 88, was first and foremost a political survivor. He survived the all-enveloping personality of his mentor, the former president Rómulo Betancourt. He survived the corruption scandals that erupted at the end of his own first presidency (1974-79). He even remained politically active after the impeachment that cut short his second term of office (1989-93). "El Gocho" – another nickname, which refers to his Andean birthplace, Rubio, in the south-western state of Táchira – was the first democratically elected president to challenge the virtual taboo on a (non-consecutive) second term in the Miraflores palace.

A comeback had scarcely seemed possible amid the suspicions aroused by his rapidly increasing personal fortune during his first presidency, when his name first began to figure on the list of Latin America's richest men. Pérez was unique among his country's presidents in another important respect: politics was his only profession. It was a vocation he took to at an early age. At 17 he met Raúl Leoni, who two years later was to co-found the social democratic Acción Democrática (AD) party – the ideal medium for Pérez's undoubted talents as a leader of the masses. In 1943 Pérez became a founder member of AD's youth section, the Juventud Adeca.

In October 1945, his national political career really took off, with his appointment as private secretary to Betancourt, the president of the ruling junta. Years of clandestine existence and conspiracy – including two spells in jail – followed the military coup of 1948, which ousted Rómulo Gallegos. In 1949 he was expelled from the country, and after returning illegally was detained and held incommunicado for six months. Deported to Panama, he travelled to Cuba to meet Betancourt and plot the overthrow of the dictator Marcos Pérez Jiménez. From 1953 to 1958 he lived in Costa Rica, where he became the editor of the newspaper La República. The Venezuela to which he returned in 1958 was a different country. An AD-led insurrection had ousted Pérez Jiménez, paving the way for decades of elected, civilian governments.

After serving as Betancourt's minister of the interior, Pérez's own turn in the presidency came after he won the December 1973 elections. The following year was marked by the birth of what became known as "Saudi Venezuela", as the global energy crisis took the price of crude oil – by far the country's biggest export – from $2 a barrel to $35 a barrel. Led by Pérez, Venezuela embarked on an orgy of costly mega-projects, alleged corruption and a grandiloquent foreign policy as the self-styled "leader of the third world". Despite unprecedented export earnings, however, the country in effect went bankrupt.

Pérez's successor, Luis Herrera Campins, declared that he had, "received a mortgaged nation". Capital flight was calculated at $35bn and the banks were pressing for repayment of a foreign debt almost as big, but whose precise size no one knew. Herrera Campins, and later Jaime Lusinchi, were forced to devalue the bolivar and renegotiate the debt, as the oil price steadily dropped.

Nevertheless, thanks to his unparalleled political skills, Pérez secured a second presidency in the 1988 elections. Offering a return to the promised land of the mid- 1970s, he crashed even more spectacularly – and promptly – than the first time. After staging a lavish and costly inauguration ceremony (dubbed "the coronation"), Pérez performed an immediate U-turn and began implementing an austerity programme that caused an instant social explosion. In the "Caracazo" riots that followed in 1989, hundreds died in the streets at the hands of troops sent to combat looters.

The second Pérez government never recovered from the unrest. The perception that his mistress and secretary, Cecilia Matos, was operating as a virtual vice-president also contributed to the disrepute into which his government declined. On 4 February 1992, he came close to being overthrown – or even assassinated – in a military coup, the first of two in less than 10 months. And although he won militarily, the political victory went to the leader of the first coup, Hugo Chávez, who would later become president.

Pérez accelerated a reform programme, including enhanced democracy at local level. But the writing was on the wall. Perceiving him to be a liability, AD bowed to the overwhelming view that he had to go. In 1993, a year before his term was due to end, he was accused of misusing government funds, and the supreme court found sufficient grounds to put him on trial. Suspended from the presidency, Pérez never wavered in his protestations of innocence. "If I were not so convinced of the transparency of my conduct," he declared, "I confess unhesitatingly that I would have preferred the other kind of death." He was convicted in May 1996 and most of his subsequent imprisonment was served in the form of house arrest, due to his age. In 1998 he returned to active politics, winning a seat in the senate.

However, the rise to power of his nemesis, Chávez, brought the abolition not only of the upper chamber but of the entire political system founded in 1958. Pérez was reduced to sniping from the political wilderness. From his self-imposed exile in New York, Miami and Santo Domingo in the Dominican Republic, he sent regular signals that he was conspiring against what he called the Chávez "dictatorship", while simultaneously denying any aspiration to return to party politics. He would set foot in Venezuela, he said, "when the time was right", regardless of any legal or physical risk he might face. That time, however, never came.

Chávez accused Pérez of leading a plot not merely to overthrow him but to assassinate him. In mid-2003, what had been verbal sparring took a different turn when the Chávez government cut off concessionary oil supplies to the Dominican Republic, on the grounds that the government of Hipólito Mejía was allowing its territory to be used for the conspiracy.

Pérez was separated from his wife, Blanca Rodríguez, with whom he had six children: Sonia, Thais, Marta, Carlos Manuel, María de los Angeles and Carolina. He also had two children with Matos, María and Cecilia.